How high are those contrails? That’s a very important issue if you are investigating the science of contrail formation. I’ve been thinking for a while that a good method might be to take photos at a plane at a known focal length on a digital camera, and then by measuring the pixels of a known dimension of the plane (the length, or the wingspan), then you could calculate the height.

So I was delighted to find that someone had already done just this, in an article titled: “Points to Ponder: Calculate the altitude of aircraft using a digital camera” (http://archive.is/kUvsB). They had worked out the math, and even given a little calculator.

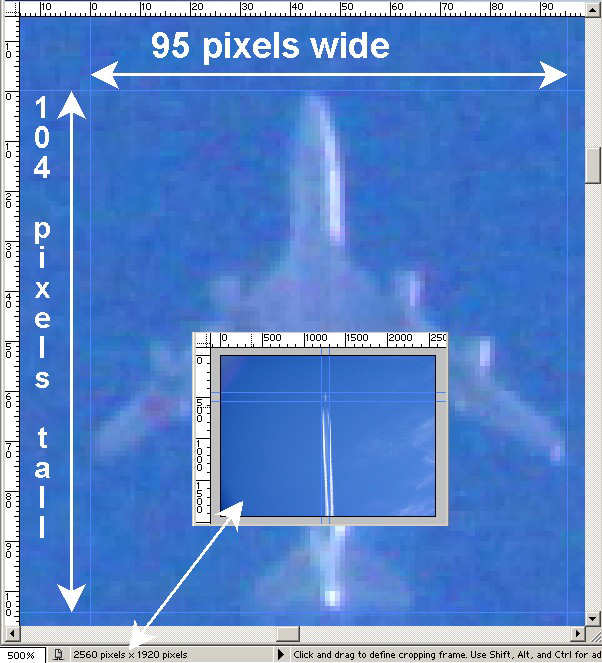

Given this photo, which is an enlargement of the inset:

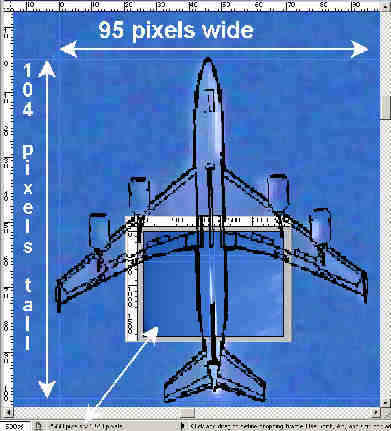

They measure the wingspan of the plane as 95 pixels, they then try to identify the plane. Being of a “chemtrail” bent, they pick a military plane, the Boeing KC-135, which has a wingspan of 131 feet. The overlaid schematic seems to match:

So using this information they calculate the height of the plane at 20,000 feet, which they then claim is too low for contrails to form. Obviously it’s not, but that’s another matter. Let’s focus on the accuracy of this calculation.

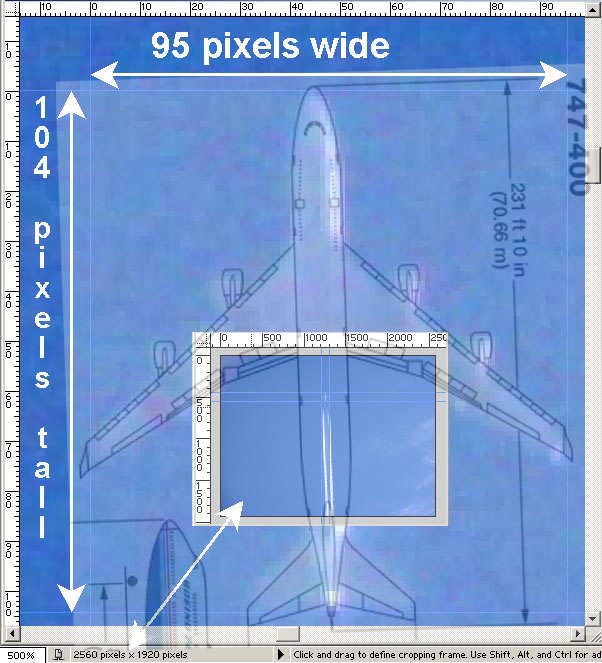

Most important here is the wingspan measurement, 131 feet. This depends on accurate identification of the plane. Is it for sure a KC-135? Well, it turns out a far more common plane fits the profile as well, the Boeing 747-400:

Note this matches a lot better than the KC-135. In particular the size of the engines is a far better match. The KC-135 engines are proportionally far bigger. The width of the plane around the nose fits a lot better. The wing angle also matches the 747 better. You can easily see it’s far more like a 747 than a KC-135.

With this better fitting plane, which has a wingspan of 211 feet, the corrected altitude would be 20000*211/131 = about 32,000 feet, roughly the cruising altitude of a Boeing 747.

To further test the accuracy of the calculation here, I calibrated my own camera at 85mm zoom (effective 136mm) by photographing a 12″ measure at a known distance (518.3 inches, laser measured) away. This came to 295 pixels. I then used this to calculate the focal length in pixels of my camera (295*518.3/12 = 12741 pixels). The focal length in pixels (f) gives you an easier method of calculating the distance (d) from image wingspan pixels (p) and wingspan in feet (w) , as it’s just d = f * p / w. I used this on a photo of a plane taking off from LAX, a known distance (4.5 miles) away (using length instead of wingspan), measured 82 pixels, and came up with a length of 151 feet (about a 737). Finally I fed everything back through the calculators supplied in the above article using their focal length & HFOV calculations , and I got back the correct distance.

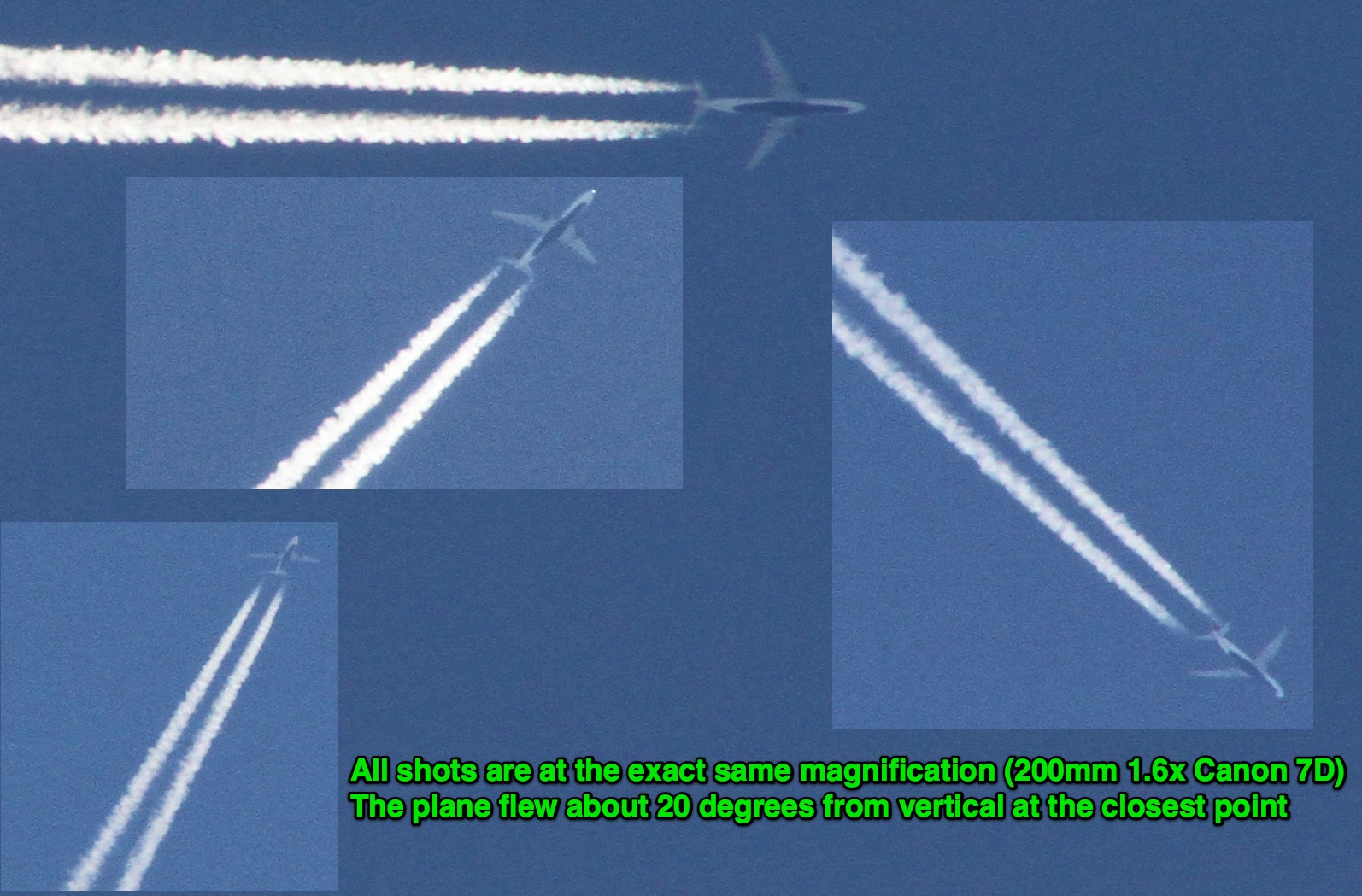

So, the math is all sound. The problem is picking your reference measurement, for which you need to correctly identify the plane. This can be quite difficult, so you should use the longest physical zoom your camera has. Most small cameras don’t have the zoom, you really need something like the equivalent of 300mm on a 35mm camera. (200 mm on a 1.6x multiplier SLR). Preferably longer.

Another thing to consider is that this gives the altitude above ground level, and the important altitude is above sea level. So if you are in Denver, add 5,000 feet, if you are in Leadville, add 10,000. Be careful not to read too much into your snapshots from the top of Mammoth Mountain (11,000 ft) either.

Another important consideration is that the altitude is only entirely accurate when the plane is directly overhead. Consider the following images, all taken at the same magnification. In each of them the plane is at the same altitude.

Comments are closed.